The Beautiful Simplicity of the Gentzen System

Oct 29, 2024

Gentzen system, created by German mathematician Gerhard Gentzen, is a deductive system which can be used to prove propositional formulas. I recently learned about it while I was reading Ben-Ari’s fantastic book on mathematical logic [1] and I like its simplicity.

Should we care about the Gentzen system? Let’s say you’re a programmer, why should you care about logic or mathematical reasoning?

I recently started learning more about mathematical logic, and I’ve realized that, just as writing can clarify your thoughts, formal mathematical reasoning can bring coherence to your thinking. If parts of your reasoning lack logical soundness, you won’t be able to construct a coherent argument as a whole—mathematical reasoning helps prevent this.

I’ve been programming for a while now, mostly self-taught, and I’ve observed that while learning mathematical formalism isn’t necessary for most programming jobs, it definitely helps you think more carefully about the correctness of your code. It helps you reason through problems with greater precision.

Now let’s dive into the Gentzen system, starting with a scenario.

Imagine you’re a detective trying to solve a robbery. To prove that a certain person committed the crime, you gather and connect key pieces of evidence. You see this person entering the house on a video camera on the day of the robbery, and you later find a receipt showing them selling items belonging to the homeowner. While real detective work is rarely this clear-cut, this simplified example highlights the deductive process of assembling truths and making logical inferences to build a case. In a similar way, a deductive system like the Gentzen system starts from basic truths and uses logical rules to reach sound conclusions.

In a deductive system, you start with basic statements assumed to be true, known as axioms, and you also apply inference rules to build a logical case. The Gentzen system stands out for its simplicity: it has just one axiom and a few inference rules, yet it can prove complex formulas. There’s a certain beauty in seeing how such a simple setup—just one axiom and a few rules—can tackle complex problems with logical precision.

Gentzen’s Genius: A Single Axiom and a Few Inference Rules

For me, what makes the Gentzen System elegant is its minimalism. Gentzen system’s approach is surprisingly simple: one axiom and just a handful of inference rules. And then you can use it to prove complex propositional formulas.

Let’s see how Gentzen system can be used to prove a propositional formula (Please note that I am teaching myself these concepts by learning from this wonderful book [1]. Any errors are my own, and I’m happy to correct anything you find incorrect. I’m writing this to reinforce my own understanding, following Confucius’ advice: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.”).

A little context about propositional logic and formulas: A propositional formula, like $ p \lor q $ (which is basically ‘p or q’, a logical disjunction), uses atomic propositions. The atomic propositions in $ p \lor q $ are $ p $ and $ q $. The atomic propositions can be assigned values $ \text{true} $ or $ \text{false} $. If $ p $ is $ \text{true} $, then $ \neg p $ (not $ p $) is $ \text{false} $. A complementary pair is a pair containing both $ p $ and $ \neg p $.

And now the axiom and a few words about inference rules.

The Axiom: Gentzen system starts with only one axiom: a complementary pair, e.g., $ p $ and $ \neg p $. That’s the only axiom in the Gentzen system.

The Inference Rules: The system also provides inference rules. These rules, alongside the one axiom, allow us to prove new things. There are two types of inference rules: $ \alpha $ (alpha) and $ \beta $ (beta). Here are some details about each of them:

$ \alpha $ inference rules: Think of these rules as ways to shape two logical formulas into a propositional formula. Let’s say you have two propositional formulas, $ A1 $ and $ A2 $, then you can combine them into a single $ \alpha $ formula. There are a few $ \alpha $ rules, but for simplicity, I’m not including them all here—they are all in Ben-Ari’s book. Let’s look at two $ \alpha $ inference rules as we will use these both in a proof below.

- If you have two formulas, $ A1 $ and $ A2 $, then you can write them as $ A1 \lor A2 $.

- If you have $ \neg A1 $ and $ A2 $, then you can write them as $ A1 \rightarrow A2 $ (A1 implies A2).

$ \beta $ inference rules: There are also a few $ \beta $ rules. Like $ \alpha $ rules, you can use them to simplify two $ \beta $ formulas. Here is one inference rule we’ll use in a proof below.

- If you have $ \neg B1 $ and $ \neg B2 $, then you can write them as $ \neg (B1 \lor B2) $.

Now, let’s try to construct a proof using the above axiom and inference rules.

We want to prove $ (p \lor q) \rightarrow (q \lor p) $ using the Gentzen system.

Basically, in such proofs, you proceed step by step, using the outcome of each step to derive the next one, eventually leading to the proof.

Prove: $ (p \lor q) \rightarrow (q \lor p) $

Here is the proof (sorry for the extra text due to the added explanation):

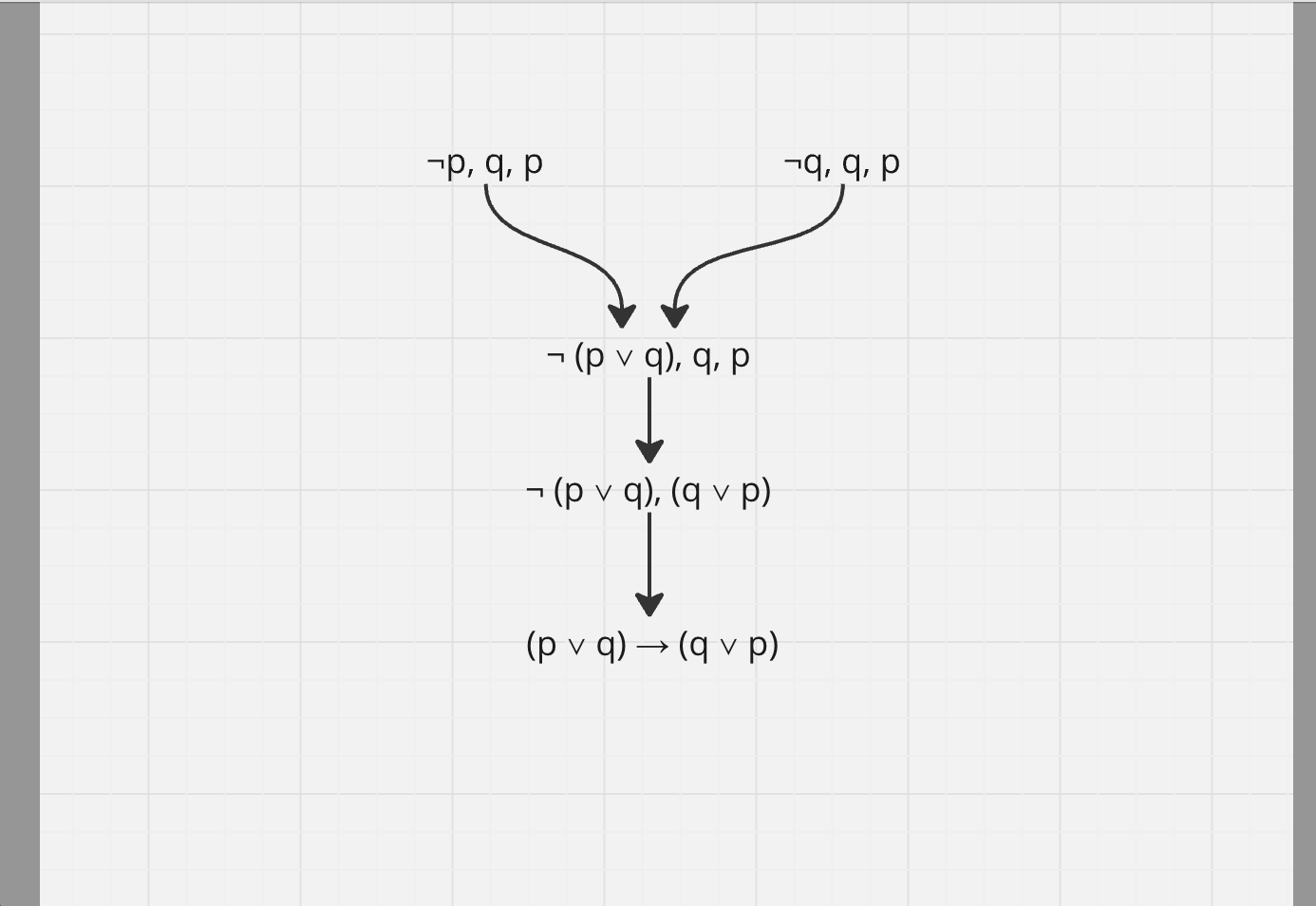

We start by examining the propositional formula we want to prove. Which atomic propositions does it invovle? Well, $ p $ and $ q $. For p, we apply the axiom, giving us both $ p $ and $ \neg p $. We then combine this with $ q $, so the outcome of the first step is: $ p, \neg p, q $.

Next, we apply the axiom again, this time for $ q $. This gives us both $ q $ and $ \neg q $. So, after the second step, we have: $ \neg q, q, p $.

Now, we can apply a $ \beta $ inference rule to the results of the first two steps. We have $ \neg p $ from the first step and $ \neg q $ from the second step. According to the $ \beta $ inference rule, if we have $ \neg B1 $ and $ \neg B2 $, we can combine them into $ \neg (B1 \lor B2) $. So, we treat $ \neg p $ as B1 and $ \neg q $ as B2. Applying the rule gives us $ \neg (p \lor q) $. The result of this third step is $ \neg (p \lor q) $, with p and q carrying over from the first two steps. Now, to explain the carryover: when we use $ \neg p $ and $ \neg q $ to form $ \neg (p \lor q) $, the remaining elements, $ p $ and $ q $, from both steps are combined with $ \neg (p \lor q) $. Since we are working with sets, we only keep unique elements, so the outcome of previous two steps is $ \neg (p \lor q), p, q $.

In this step, we apply an $ \alpha $ rule. According to this rule, if we have A1 and A2, we can combine them into $ A1 \lor A2 $. From step 3, we have $ q $ and $ p $. Applying the alpha rule to these two propositions gives us $ q \lor p $. Importantly,

$ \neg (p \lor q) $ is unchanged, so it carries over. The result of this step is: $ \neg (p \lor q), (q \lor p) $.Now, let’s look at what the result of step 4. Can we apply a rule to get the formula we set out to prove? Yes! We can use another $ \alpha $ rule, which says if we have $ \neg A1 $ and $ A2 $, we can form $ A1 \rightarrow A2 $ (A1 implies A2). In step 4, we have $ \neg (p \lor q) $ as $ \neg A1 $ and $ (q \lor p) $ as $ A2 $. Using this rule, we arrive at $ (p \lor q) \rightarrow (q \lor p) $, which is exactly what we set out to prove. Voila!

Here is a brief summary of the above steps. In the first two steps of the proof below, we start with axioms. Then, in the third step, we apply the $ \beta $ inference rule on the the outcome of the first and second step. Then, on the result of the third step, we apply an $ \alpha $ inference rule. Finally, on the outcome of the fourth step, we apply another $ \alpha $ rule, and we are be able to prove what we set out to prove.

At first, I didn’t understand this by just reading it—it seemed too clever (as the author also hinted that it seemed clever). I had to solve it a couple of times using pen and paper.

This can also be presented in the tree form. In the screenshot below, the top nodes are axioms, the internal nodes are inference rules, and the node at the bottom is the formula that needed to be proved:

There is an inexplicable beauty in the idea that you start with only one established truth and a few inference rules, and using them, you can prove complex propositional formulas.

Creating a system with just one axiom and a few inference rules that can prove complex propositional formulas is a sign of elegance. The idea that we can take basic truths and use them to prove more complex things has a certain elegance. The idea that we can discipline our thinking in steps, with each rule application or inference bringing us closer to our goal while maintaining a coherent structure, also embodies elegance. This kind of elegance can inspire us to learn and master complexity in other fields.

Please email or tweet with questions, ideas, or corrections.

References:

- Mathematical Logic for Computer Science by Mordechai Ben-Ari, 3rd edition.