How to Solve Santa Claus Concurrency Puzzle with a Model Checker

Jan 10, 2026

When I enjoy a book, I often look for other work by the same author. While reading a book by Ben-Ari, I looked up his other writing and came across a paper on the Santa Claus concurrency puzzle 1. The puzzle is stated as follows:

Santa Claus sleeps at the North Pole until awakened by either all nine reindeer or a group of three out of ten elves. He performs one of two indivisible actions:

- If awakened by the group of reindeer, Santa harnesses them to a sleigh, delivers toys, and finally unharnesses the reindeer, who then go on vacation.

- If awakened by a group of elves, Santa shows them into his office, consults with them on toy R&D, and finally shows them out so they can return to work constructing toys.

A waiting group of reindeer must be served by Santa before a waiting group of elves. Since Santa’s time is extremely valuable, marshalling the reindeer or elves into a group must not be done by Santa.

The puzzle captures the kind of synchronization challenges that arise whenever multiple processes must coordinate. I wanted to validate its correctness using a model checker. I expected this to be a simple problem. What surprised me is how easy it is to get it wrong.

I also chose a different path to the solution. Before writing the correct model, I spent some time exploring what incorrect designs might look like. I find failures instructive because they expose unsafe assumptions and make clear what a correct solution must prevent. As a learning exercise, I wrote three small models, each reproducing a different failure scenario, and used correctness properties to catch the bugs. We will look at these failures in a bit. After that, I present the correct model and validate it with a model checker.

To carry out this analysis, I used the SPIN model checker and wrote the models in Promela, SPIN’s specification language.

A natural question is why use a model checker instead of simply writing the solution in Python or Go. The answer is coverage: a model checker explores interleavings that tests or experiments might miss, and either proves correctness or produces a counterexample.

Let’s look at three key puzzle constraints:

Santa must not marshal the groups himself.

If both reindeer and elves are waiting, Santa must serve the reindeer first (Christmas delivery is critical).

When Santa serves a group, the entire group must participate together: exactly nine reindeer for delivery, or exactly three elves for consultation. Santa cannot deliver toys with seven reindeer or consult with two elves, for example.

At first, the problem seems straightforward. You wait until nine reindeer arrive or three elves arrive, wake Santa, do the work, and repeat. It is tempting to think that a few counters or locks are enough to solve it. The difficulty is in the interleavings. A solution that appears correct when reasoning step by step can fail when operations interleave in unexpected ways.

Let’s now consider three failure scenarios that solve the puzzle incorrectly.

- Santa delivers toys even though fewer than nine reindeer are actually ready.

- Under a subtle interleaving, Santa ends up doing something impossible in the real world: delivering toys and consulting with elves at the same time.

- Santa chooses to consult with elves even though nine reindeer are already waiting and ready to go.

We’ll look at each of these failure scenarios next, and then work toward a solution that satisfies all puzzle constraints. Before that, let’s briefly introduce the Promela concepts we’ll need: channels, options, and guards.

To communicate between processes, we use channels in Promela. A channel is a data type that supports two operations: send and receive. Channels transfer messages of a specified type from a sender to a receiver.

SPIN supports two kinds of channels: rendezvous channels and buffered channels. In a rendezvous channel, send and receive synchronize: the sender blocks until the receiver is ready (and vice versa), and the transfer occurs as one atomic handshake. Buffered channels can hold messages temporarily, even if no process is ready to receive them yet. Buffered channels let a sender run ahead of a receiver; rendezvous channels force them to move together.

A send operation consists of a channel variable followed by an exclamation mark (!) and a sequence of expressions whose number and types must match the channel’s message type. A receive operation, by contrast, consists of a channel variable followed by a question mark (?) and a sequence of variables into which the message is received.

For example, we can declare a rendezvous channel named request that carries messages of type byte as follows (rendezvous channels have capacity of 0 as indicated by [0] syntax):

chan request = [0] of { byte };

We can send data on this channel as:

request ! 1

and receive data as:

byte client;

request ? client

Now a few words about options and guards. Options in Promela can be used to do branching in the code. For example, one could write an if statement in Promela as:

if

:: (a < 50) -> printf("a < 50\n");

:: (a > 50) -> printf("a > 50\n");

fi

Each line beginning with :: is an option. An option consists of a guard followed by an action. The guard is the Boolean expression before the arrow (->). An option is enabled if its guard evaluates to true.

When the if statement is reached:

if exactly one option is enabled, Promela takes that option;

if multiple options are enabled, SPIN may choose any one of them nondeterministically;

if no option is enabled, the process blocks at the if.

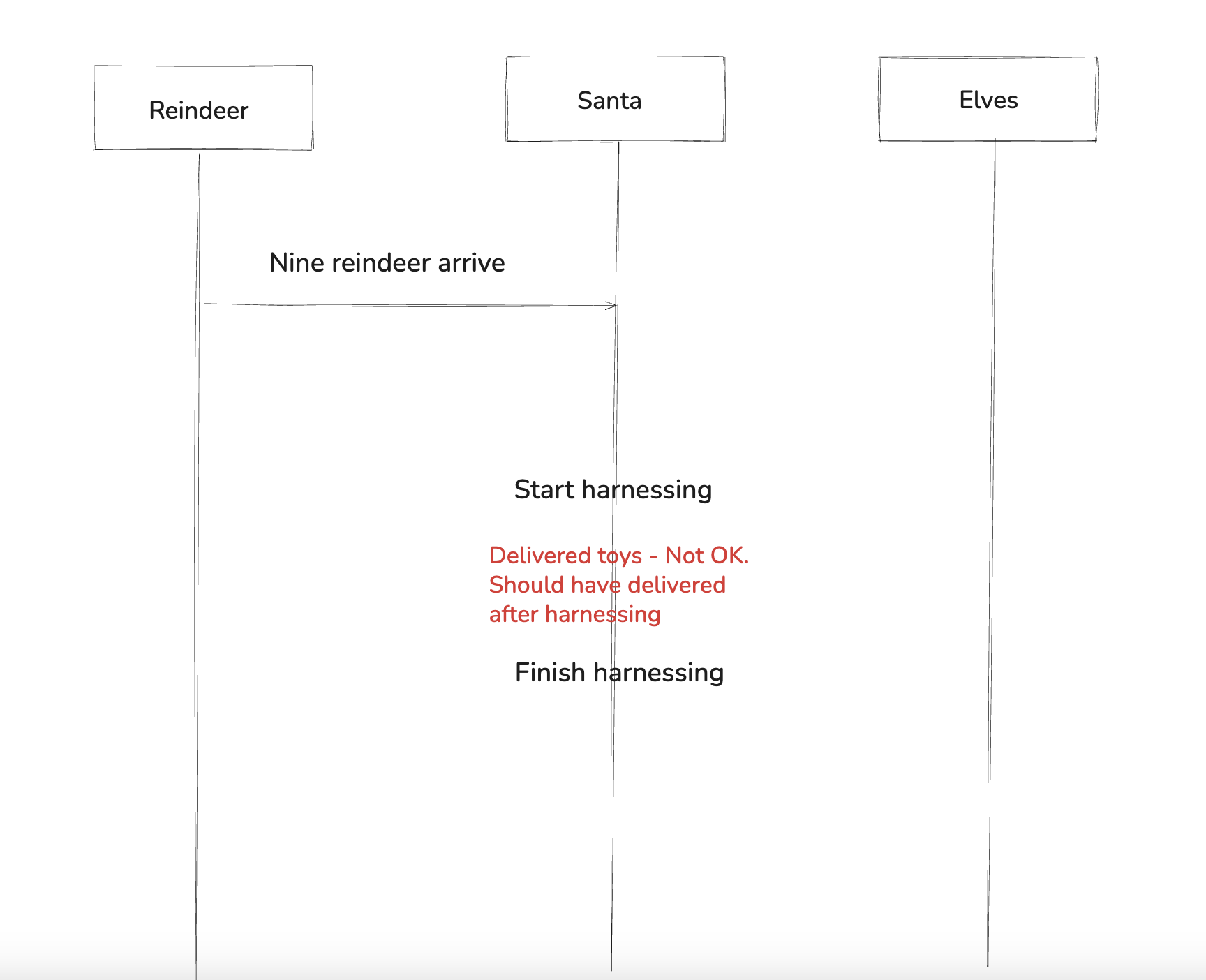

Now let’s look at the first failure scenario in which Santa may deliver toys without all nine reindeer being ready. In the failure models I sometimes shrink the number of elves (e.g., to 3) to keep the state space small; the failure mechanism is the same.

Here is a code excerpt from the model that simulates the first failure scenario:

#define NUM_REINDEER 9

#define NUM_ELVES 3

// buffered channels

chan harnessed = [NUM_REINDEER] of { bit };

chan done_consulting = [NUM_ELVES] of { bit };

// Some code omitted for brevity

active [NUM_REINDEER] proctype Reindeer()

{

do

::

r_arrive ! 1;

harnessed ? 1;

actually_harnessed++;

actually_harnessed--;

od

}

active proctype Santa()

{

byte i = 0;

byte e = 0;

byte j;

do

:: (i < NUM_REINDEER) ->

r_arrive ? 1;

i++;

if

:: (i == NUM_REINDEER) -> reindeer_ready = true

:: else -> skip

fi

:: (i == NUM_REINDEER) ->

for (j : 1 .. NUM_REINDEER) {

harnessed ! 1;

}

delivering = true;

/*

simulating delivering toys

*/

delivering = false;

reindeer_ready = false;

i = 0;

// Some code omitted for brevity - complete code linked below

}

// Correctness property

ltl safety { [] (delivering -> actually_harnessed == NUM_REINDEER) }

This Promela model is a small “executable spec” of the Santa problem. The full model and instructions for running it are available in the repository 2. To keep things simple, I mainly discuss the Santa–reindeer interaction; elves are present only to keep the overall structure similar.

The syntax active [N] proctype P(){…} tells SPIN to start N concurrent copies of process P in the initial state, so here you get 9 Reindeer processes, 3 Elves processes, and 1 Santa process. Each reindeer loops by rendezvous-sending on the r_arrive channel, so it blocks until Santa receives, then waits for a harness message on harnessed. Santa loops, counting reindeer arrivals. Once all nine reindeer have arrived, he “harnesses” them by sending nine messages on harnessed and then briefly sets delivering = true to represent toy delivery.

The bug is that harnessed is a buffered channel, so Santa can enqueue all nine harness messages and immediately proceed; nothing forces the reindeer to have actually received them yet. That violates the puzzle constraint that Santa must deliver with the whole group participating together. To check whether this implementation respects the puzzle’s constraints, we write correctness properties in Linear Temporal Logic (LTL).

In simple terms, an LTL property describes a rule that must hold over time as the system runs. The model checker constructs the system’s state space by enumerating all reachable states, each state being a snapshot of all variables and the current position of each process in its code, under all possible interleavings. You can think of this state space as a graph: each node is a state, and each edge represents a single step the program can take as processes interleave. An LTL property is then checked against this entire state space: when we say a condition must “always” hold, we mean it must be true in every reachable state that SPIN explores.

The LTL property ltl safety { [] (delivering -> actually_harnessed == NUM_REINDEER) } encodes that requirement. Here [] means “always,” so the property states that in every reachable state, if delivering is true, then all nine reindeer must already be harnessed.

When SPIN checks this property, it finds an execution in which Santa sets delivering = true before all nine reindeer have received their harness signals. In other words, Santa starts delivering toys while some reindeer are still unharnessed. The property fails, and SPIN produces a counterexample showing exactly how this execution occurs. The code shows this model, along with instructions for running it and viewing the trace that contains the counterexample.

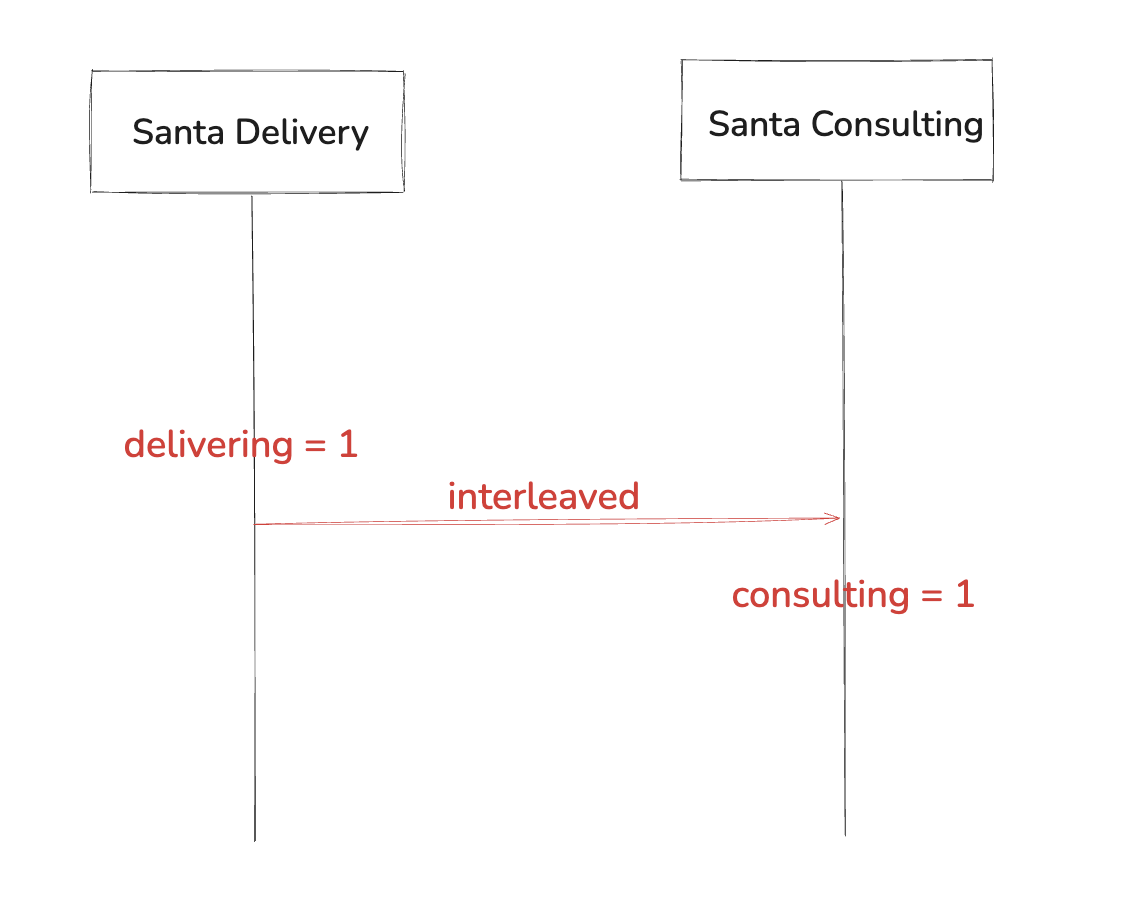

Now let’s look at a second failure scenario, in which Santa may end up doing the seemingly impossible, delivering toys with the reindeer and consulting with the elves at the same time. The complete model that simulates this fault is available here 3; an excerpt is shown below.

To make this bug easy to trigger, I did something silly: I split Santa into two: one responsible for toy delivery and one for consultation. Each process independently waits for its own group to form and then sets the corresponding flag (delivering or consulting) to indicate that work has begun. Because these two processes run concurrently and share no mutual exclusion, there exists an interleaving in which both flags become true at the same time.

The code violates a core constraint of the puzzle: Santa must perform only one indivisible action at a time. By adding an assert statement that asserts Santa never delivers and consults simultaneously, SPIN is able to find a concrete counterexample trace showing exactly how this impossible situation arises under a particular interleaving.

active proctype SantaConsulting()

{

byte e = 0;

byte j;

end:

do

:: (e < NUM_ELVES) ->

e_arrive ? 1;

e++;

:: (e == NUM_ELVES) ->

consulting = true;

assert !(consulting && delivering);

// We release elves here

consulting = false;

e = 0;

od

}

active proctype SantaToyDelivery()

{

byte i = 0;

byte j=0;

end:

do

:: (i < NUM_REINDEER) ->

r_arrive ? 1;

i++;

:: (i == NUM_REINDEER) ->

delivering = true;

// We release the reindeer here

delivering = false;

i = 0;

od

}

// correctness property

ltl reindeer_precedence {

[] ( (r_count == NUM_REINDEER) -> ( (!consulting) U delivering ) )

}

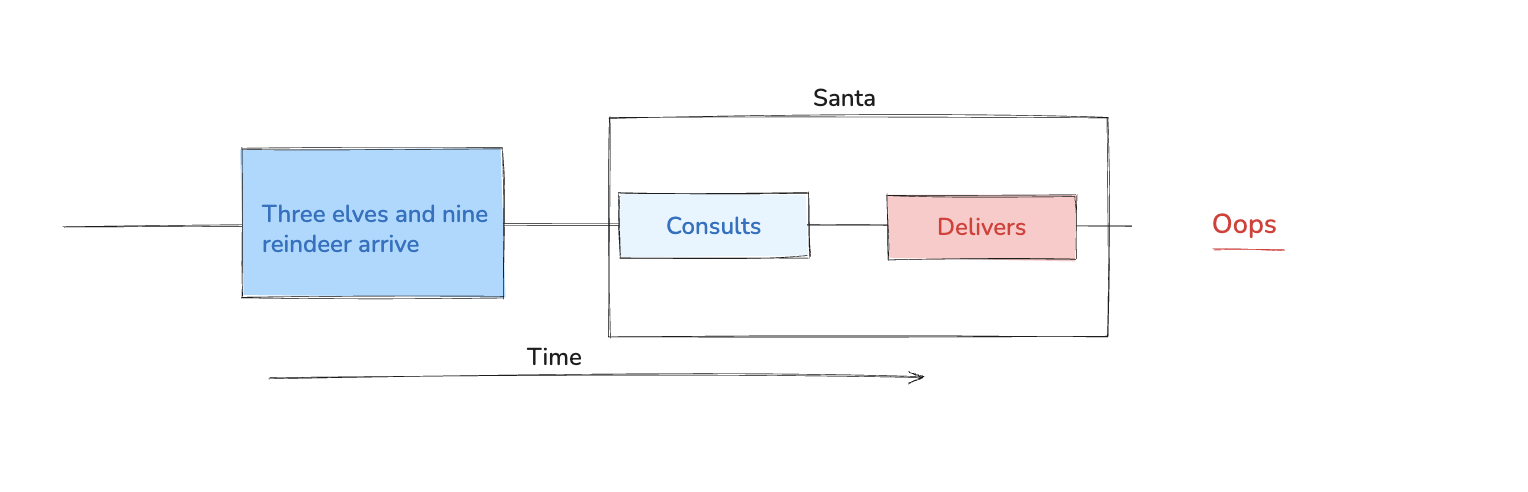

Now let’s examine the final failure scenario, in which Santa may consult with elves even when a full group of nine reindeer is already waiting. The complete model that simulates this fault is available here 4; structurally, it is very similar to the previous one.

In this version, Santa’s consultation logic does not check whether a full reindeer group is ready before proceeding. As a result, there exists an interleaving in which all nine reindeer have arrived and a group of three elves is also ready, yet Santa begins consulting with the elves. This violates a central constraint of the puzzle: when both groups are waiting, reindeer must be served before elves.

I found it tricky to detect this using only the tools discussed so far, and then discovered a precedence property expressed in LTL. Informally, the property states: once a full group of nine reindeer is ready, consulting must not occur before delivery begins. We encode this using the LTL ‘until’ operator (written as ‘U’), which lets us state that consulting must remain false until delivery occurs. When SPIN checks this property, it finds a counterexample in which Santa consults first, demonstrating that the implementation violates the required precedence rule.

There’s one more rule that all of the models above break: Santa must not do the marshalling himself. In the above models, Santa is directly counting arrivals and releasing reindeer and elves, which makes it easy to mix up group formation with the work itself.

The fix is to give Santa some help. Following Ben-Ari 1, we introduce rooms. A room’s only job is to collect arrivals and let Santa know when a complete group is ready. Santa never counts arrivals anymore, he simply waits for a “group ready” signal and then does the work.

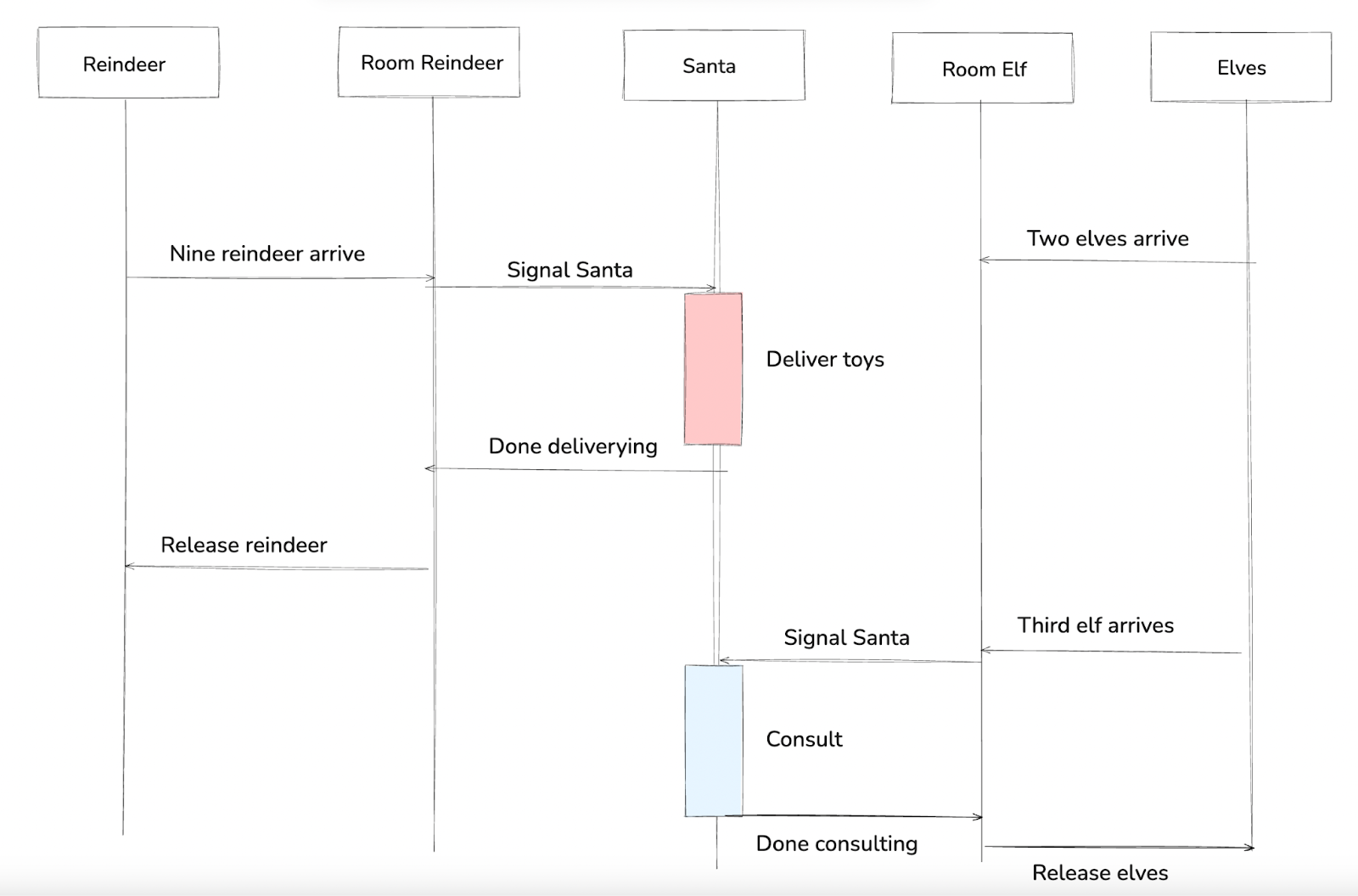

To build a correct model, we use one room for the reindeer and another for the elves. The key idea is to separate marshalling (handled by the rooms) from serving. Let’s now look at the modified sequence of events.

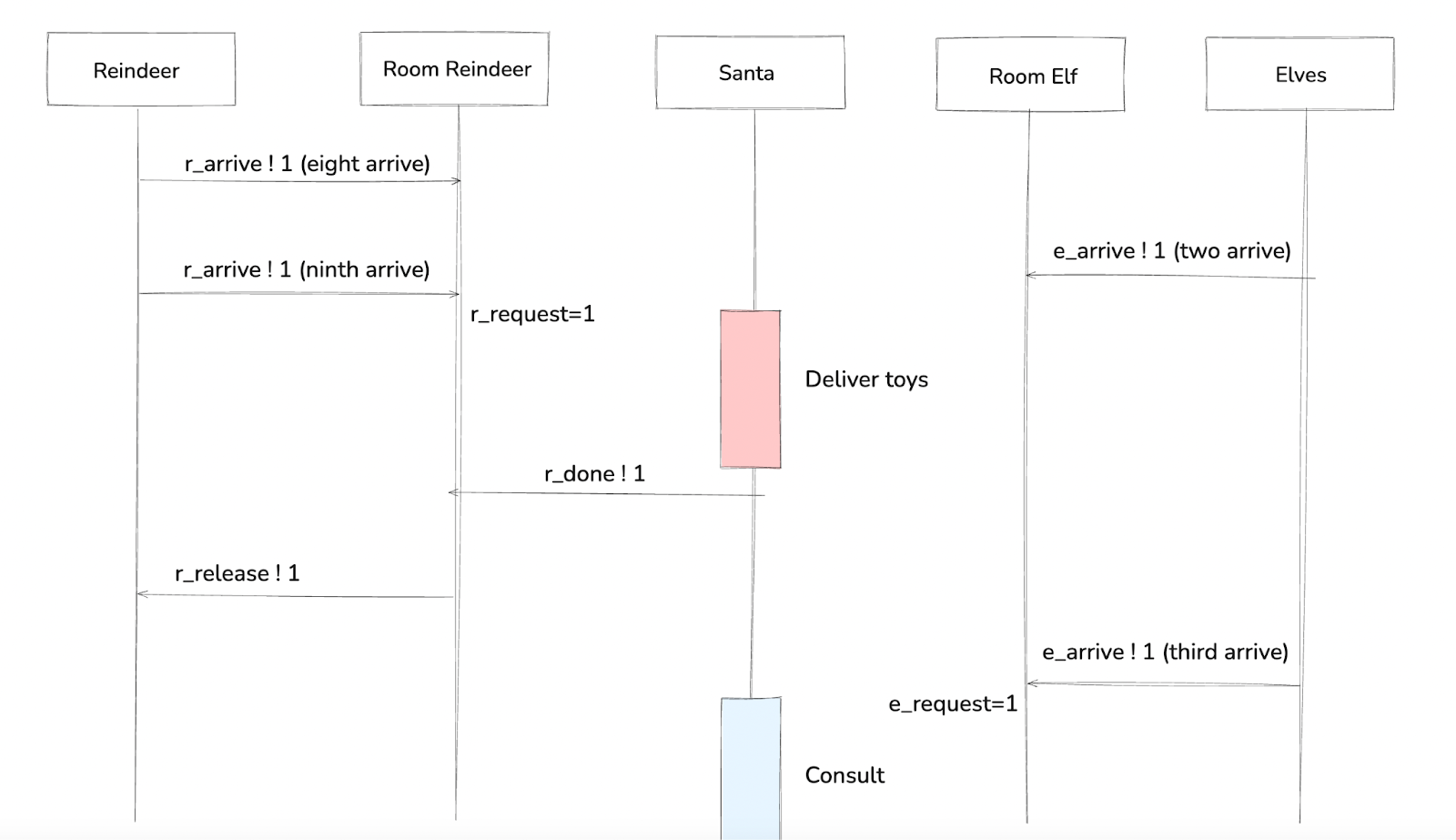

When a group of nine reindeer arrives at the reindeer room, the room signals Santa. While this is happening, two elves also arrive. Santa delivers toys and releases the reindeer. When the third elf later arrives, the elf room signals Santa; Santa consults with the elves and then releases them.

To model this behavior in SPIN, each component is represented as a separate process. SPIN explores all possible interleavings of these processes and checks that specified correctness properties hold in every reachable state.

We model the system using the following processes:

Reindeer: We run nine reindeer processes concurrently. Each reindeer arrives at the reindeer room and waits there until it is released.

Elves: We also run ten elf processes concurrently. Each elf arrives at the elf room and waits there until it is released.

Reindeer room: We run a single instance of this process, which simulates the reindeer room. It collects arriving reindeer, signals Santa when a full group of nine has formed, and releases the group after Santa completes delivery.

Elf room: Similarly, we run a single instance of this process to simulate the elf room. It collects arriving elves, signals Santa when a group of three has formed, and releases the group after Santa completes consultation.

Santa: A single Santa process waits for “group ready” signals from the rooms. It serves reindeer with priority over elves and notifies the appropriate room when its work is complete.

To communicate between processes, we use the following rendezvous channels, each carrying messages of type bit:

chan r_arrive = [0] of { bit };

chan e_arrive = [0] of { bit };

chan r_release = [0] of { bit };

chan e_release = [0] of { bit };

chan r_done = [0] of { bit };

chan e_done = [0] of { bit };

We append an r to channel names that transfer data for reindeer, and an e to those for elves. Below are the roles of the main channels:

r_arrive / e_arrive: These rendezvous channels represent how reindeer and elves enter their rooms. A reindeer tries to enter by sending on r_arrive; because the channel is rendezvous, it blocks until the room is ready to receive. When the room is full, it stops receiving arrivals, so additional reindeer (or elves) block until the room re-opens.

r_release / e_release: These channels represent how a room releases a complete group. After Santa finishes, the room sends on r_release (or e_release) once per group member. Because the channel is rendezvous, the room cannot “release ahead”, each send synchronizes with an actual waiting reindeer (or elf).

r_done / e_done: These channels represent Santa’s “I’m finished” notification to the room. The room waits for this signal before releasing anyone. For example, after Santa finishes delivering toys, he sends on r_done; without it, the room would not know when it is safe to release the reindeer.

Now let’s look at the reindeer and elf processes, which are quite similar. We’ll start with the reindeer process:

active [9] proctype Reindeer()

{

do

:: r_arrive ! 1; // enter the room

r_release ? 1; // wait to be released

od

}

Because of the active [9] keyword, SPIN starts nine reindeer processes running concurrently in the initial system state. The statement r_arrive ! 1 indicates that a reindeer is attempting to enter the reindeer room by sending on the r_arrive channel. Because r_arrive is a rendezvous channel, the reindeer blocks until the room is ready to accept it. After entering the room, the reindeer waits to be released by blocking on the r_release channel.

The code for the elf process is similar:

active [10] proctype Elf()

{

do

:: e_arrive ! 1;

e_release ? 1;

od

}

The room is where marshalling and synchronization take place. Let’s now look at the reindeer room.

active proctype RoomReindeer()

{

byte waiting = 0;

byte i = 0;

do

/* Collect reindeer until the group is complete (entrance open iff waiting < 9) */

:: (waiting < NUM_REINDEER) ->

atomic {

r_arrive ? 1;

waiting++;

reindeer_waiting = waiting;

if

:: (waiting == NUM_REINDEER) -> r_request = 1

:: else -> skip

fi

}

/* Group complete: wait for Santa, then release all 9 and reset */

:: (waiting == NUM_REINDEER) ->

atomic { r_done ? 1; i = 0; }

do

:: (i < NUM_REINDEER) ->

atomic { r_release ! 1; i++; }

:: else -> break

od;

atomic {

waiting = 0;

reindeer_waiting = 0;

}

od

}

The repetition structure has two alternatives. When waiting is less than NUM_REINDEER, the room accepts arriving reindeer and increments the counter. If the arrival completes the group, the room sets r_request = 1 to notify Santa.

When waiting equals NUM_REINDEER, the room stops accepting arrivals and waits for Santa to message completion on r_done. After receiving this message, the room releases the reindeer via r_release and resets its state to accept new arrivals.

The logic for the elf room follows the same pattern and is omitted here for brevity.

The Santa process models two kinds of work: toy delivery with the reindeer and consultation with the elves. Its main loop contains two guarded alternatives.

In the first alternative, guarded by r_request, Santa performs the toy delivery action, clears r_request, and signals completion to the reindeer room by sending on r_done. The corresponding code is shown below.

:: r_request ->

atomic {

delivering = true;

r_request = 0; /* claim the request */

}

/* Deliver toys (abstracted). */

delivering = false;

/* Notify the Room that delivery is complete; it can release the reindeer. */

r_done ! 1;

The second alternative is guarded by !r_request && e_request. This guard enforces the priority rule: Santa consults with the elves only if no reindeer group is waiting and a group of three elves has formed. Santa then performs the consultation and signals completion to the elf room by sending on e_done.

:: (!r_request && e_request) ->

atomic {

consulting = true;

e_request = 0; /* claim the request */

}

/* Consult (abstracted). */

consulting = false;

/* Notify the Room that consultation is complete; it can release the elves. */

e_done ! 1;

How do we validate that the model is correct?

We can specify two kinds of correctness properties: safety properties and liveness properties. Let’s look at them one by one.

Safety properties assert that nothing bad ever happens. We use three safety properties in this model. First, we ensure that Santa always delivers toys with exactly nine reindeer, that is, a full group of nine reindeer must be present in the room. We specify this as:

ltl safety_delivery { [] (delivering -> reindeer_waiting == 9) }

This property states that, at all times, if Santa is delivering toys, then the variable reindeer_waiting must equal 9.

Second, we ensure that Santa always consults with exactly three elves. We specify this as:

ltl safety_consult { [] (consulting -> elf_waiting == 3) }

Finally, we specify a mutual-exclusion property to ensure that Santa never delivers toys and consults at the same time:

ltl mutex_santa { [] !(delivering && consulting) }

You might wonder why the variables delivering and consulting are set to true only briefly. In this model, delivery and consultation are not simulated in detail, they are represented as single abstract steps. The boolean flags simply mark the moment when Santa starts a delivery or consultation, so that we can state and check correctness properties. Their purpose is not to model time passing, but to make illegal overlaps visible to the model checker.

Now let’s turn to the liveness property. Liveness properties state that something good eventually happens. The liveness property we specify is: always, if a request is pending, then eventually Santa will either be delivering toys or consulting with elves. This rules out executions where requests remain pending forever without Santa ever doing work.

We specify this property as follows (where [] denotes “always” and <> denotes “eventually”):

ltl live_progress { [] ((r_request || e_request) -> <> (delivering || consulting)) }

One important role of a liveness property is to avoid vacuous correctness. For example, a safety property such as [] (delivering -> reindeer_waiting == 9) can hold even if delivering is never true (‘->’ is an implication, and in logic an implication “A implies B” is considered true whenever A is false, regardless of whether B is true or false.). In contrast, this liveness property rules out executions where a request remains pending forever without Santa ever taking a delivery or consultation step, in other words, it checks that some service step eventually occurs whenever a request is pending.

When we run the model in SPIN, all safety and liveness properties pass. In separate runs, SPIN explored about 5 million states while checking safety_delivery and mutex_santa, and about 7 million states while checking the liveness property and found no counterexamples. In a similar fashion, we can also specify and check the precedence property.

Both the model and the instructions for running it are available in the repository 5.

Let’s now look at an example execution to see how these pieces fit together.

Time flows from top to bottom. When the ninth reindeer arrives, the reindeer room sets r_request and closes the room to further arrivals. While r_request remains true, Santa serves the reindeer, even if elves arrive, because the elf branch is disabled by the guard !r_request.

After Santa signals completion by sending on r_done, the room releases all nine reindeer via rendezvous. When a group of three elves later forms, the model sets e_request. Since r_request is now false, Santa serves the elves.

To transform this model into a computer program, I thought I would try implementing it in Go. I do not know Go particularly well, so I collaborated with an AI to translate the Promela design into a simple, idiomatic Go implementation. I reviewed the code 6 to keep it faithful to the model, but any mistakes are mine.

Please keep in mind that I’m only human, and there’s a chance this post contains errors. If you notice anything off, I’d appreciate a correction. Please feel free to send me an email.

Endnotes:

Ben-Ari, M. How to Solve the Santa Claus Problem. Concurrency: Practice and Experience, 1998. ↩ ↩2

Link to the source code for the first failure scenario: https://github.com/wyounas/model-checking/blob/main/puzzles/santa_claus/santa_bug_deliver_without_full_group.pml ↩

Link to the source code for the second failure scenario: https://github.com/wyounas/model-checking/blob/main/puzzles/santa_claus/santa_bug_deliver_and_consult_simultaneously.pml ↩

Link to the source code for the third failure scenario: https://github.com/wyounas/model-checking/blob/main/puzzles/santa_claus/santa_bug_consult_before_delivery.pml ↩

Link to the source code for the room-based solution: https://github.com/wyounas/model-checking/blob/main/puzzles/santa_claus/santa_claus.pml ↩

Link to the Go implementation of the room-based solution: https://github.com/wyounas/model-checking/blob/main/puzzles/santa_claus/santa_claus.go ↩