How Rendezvous Channels Work in PROMELA (SPIN)

Nov 18, 2024

PROMELA is a language used to write models that can be validated with the SPIN model checker. To facilitate data exchange between processes, PROMELA provides the concept of channels. These channels are essential when creating a model where processes need to communicate and share data.

Channels allow two processes to exchange information. One process can send data through a channel, and another process can receive it from the same channel. In PROMELA, there are two types of channels:

- Rendezvous channels: These have zero capacity and require both sender and receiver to synchronize.

- Buffered channels: These have a capacity greater than zero and can store messages until they are read.

In this blog, we’ll focus on rendezvous channels.

In PROMELA, you can initialize channels using the following syntax:

chan channelname = [capacity] of {typename}

For example, you can create a rendezvous channel of type byte like this (meaning the channel can send and receive data of type byte):

chan ch = [0] of {byte}

Rendezvous channels have a capacity of zero. I think of a zero-capacity channel as a medium that simply exchanges data without storing it, since it has no capacity to hold messages.

To send a value on the channel, you use a send statement, which consists of the channel variable followed by an exclamation mark (!), and then the message value. For example, the following statement sends the value 10 on the channel we created earlier:

ch ! 10

To receive a value, you use a receive statement, which consists of the channel variable followed by a question mark (?), and then the variable where the received value will be stored. For example:

byte value

ch ? value

In this example, the channel ch facilitates a handshake followed by the transfer of the value. Communication via a rendezvous channel is synchronous, meaning only two processes can engage in the handshake at a time.

When writing models, one process may send data while another receives it. If a rendezvous channel’s “send” statement is executed but there is no matching “receive” statement, the sending process will block. Similarly, a process with a “receive” statement will block if there is no matching “send” statement.

Here’s an example where a value is sent but never received:

chan ch = [0] of {byte}; // Rendezvous channel

active proctype Sender() {

ch ! 10

}

In this case, the Sender process will block indefinitely because there is no corresponding receive statement. (To run above code, save the code in “file.pml” and then run “spin file.pml” on the command prompt.)

Now, let’s walk through an example to understand how rendezvous channels work. Imagine we have two processes: a sender and a receiver.

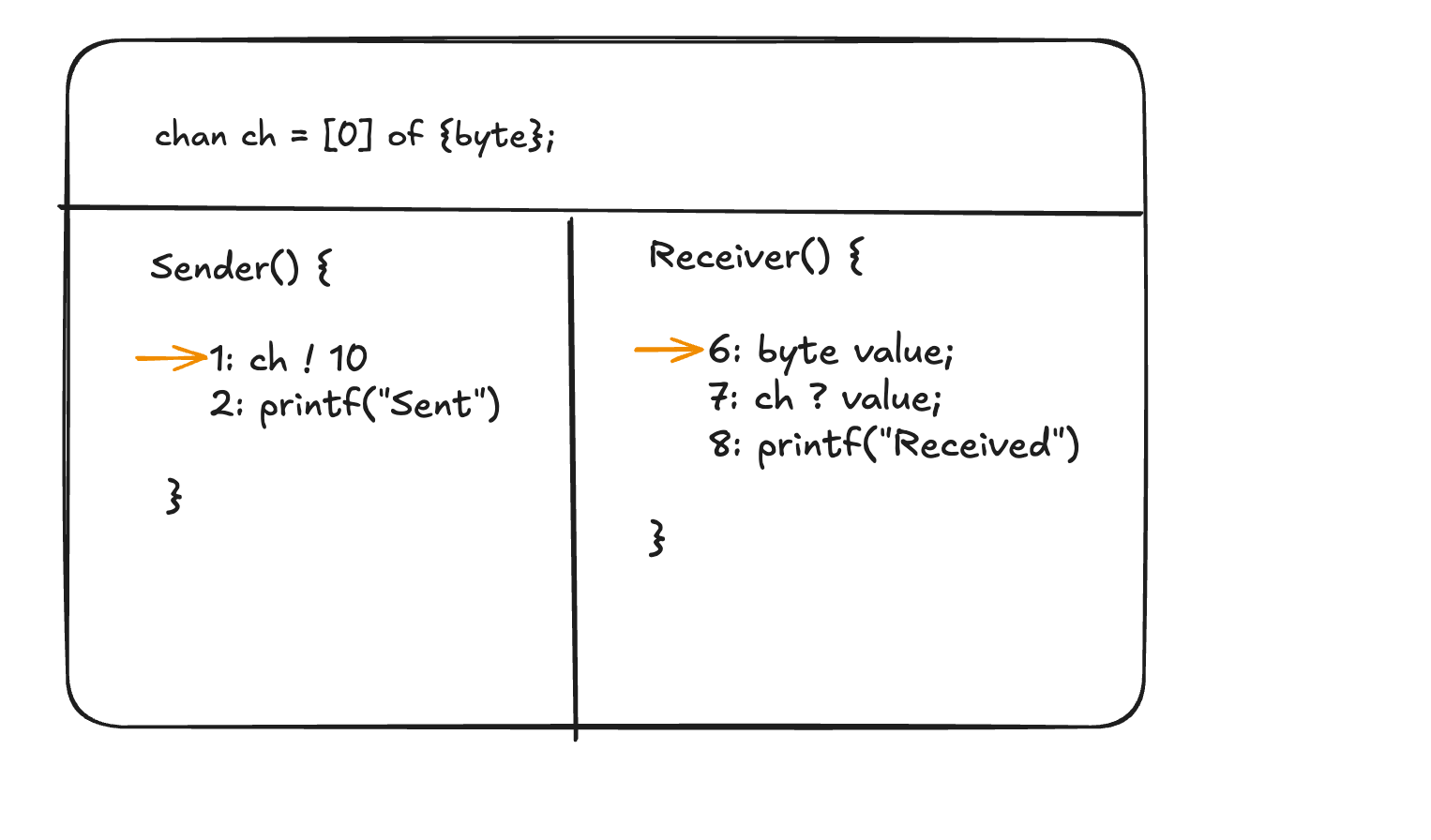

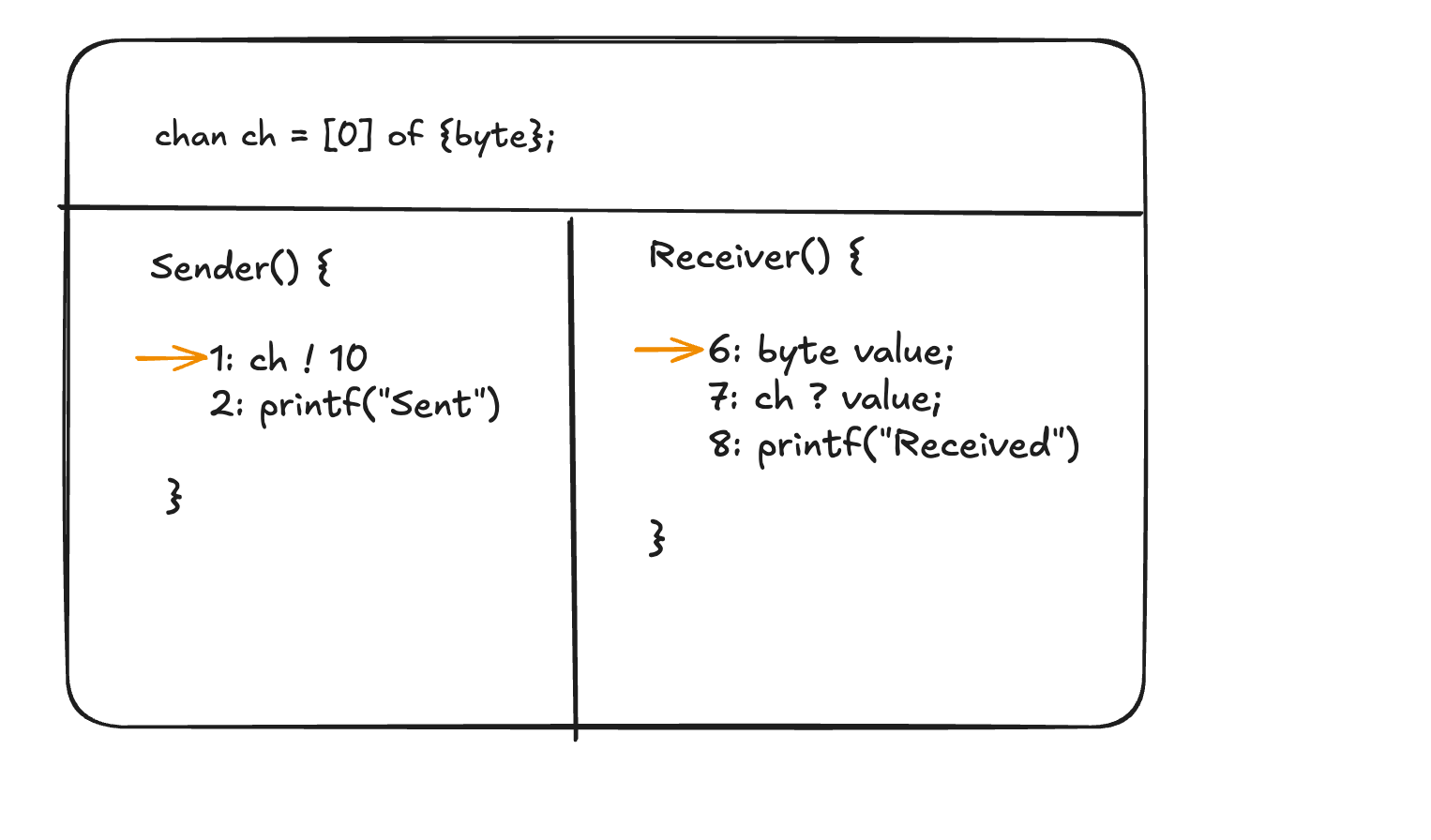

The Sender process sends a value on a rendezvous channel named ch, while the Receiver process receives this value from the channel and stores it in a local variable named value. The orange arrows represent the location counters, which indicate the next instruction to be executed in each process. The numbers 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 are the specific locations where the location counter can point. Initially, both counters are assumed to point to the first instructions in their respective processes.

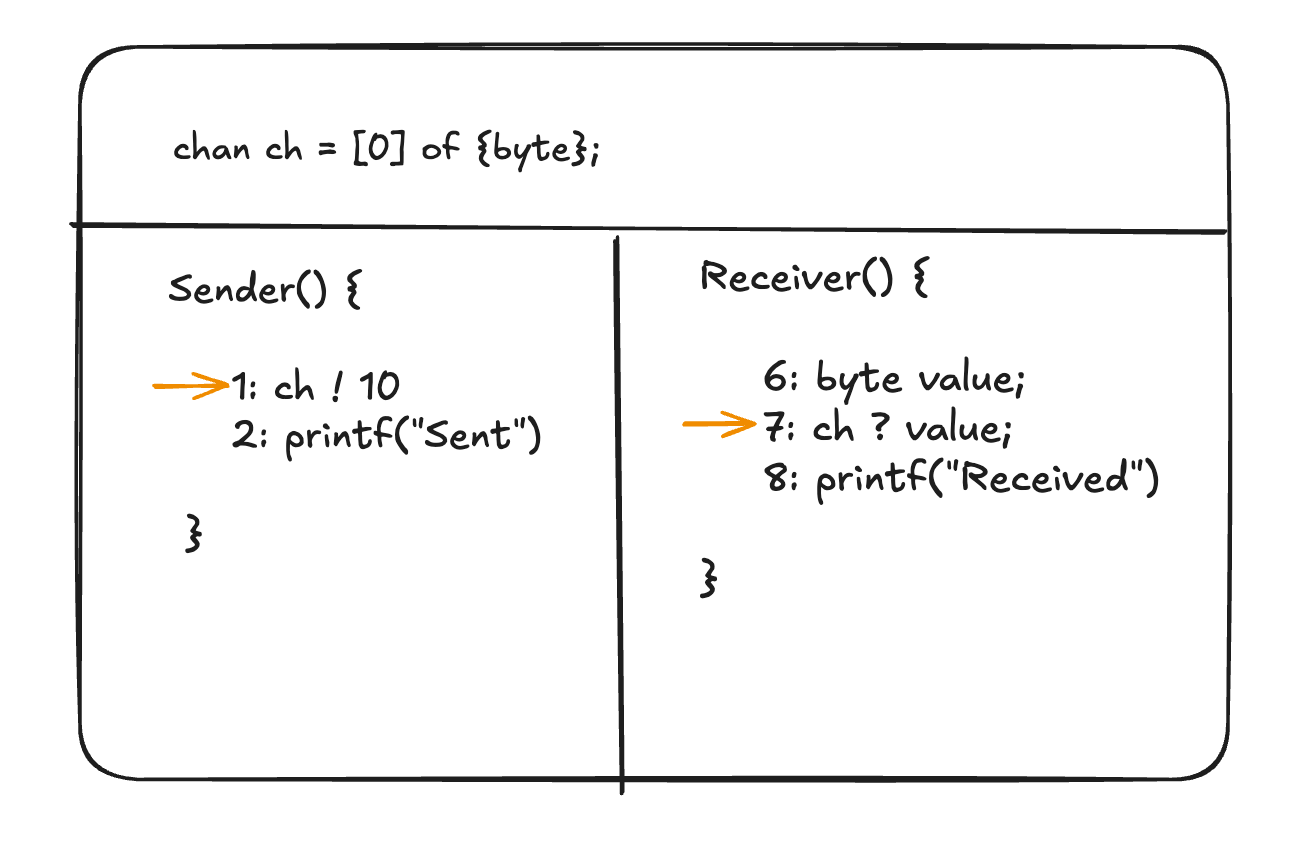

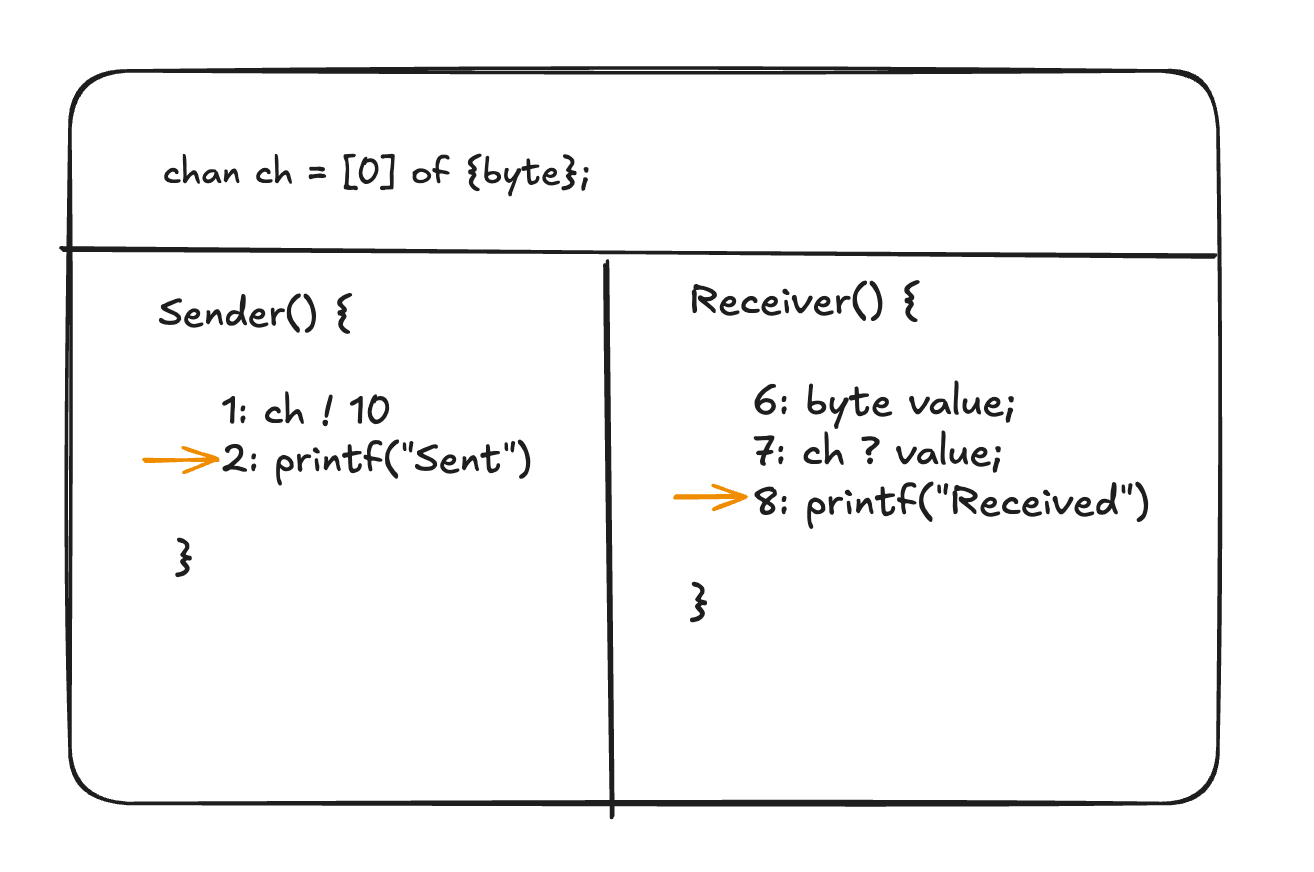

When the location counter of the Sender process reaches the channel’s send statement, it offers to engage in a rendezvous. If the location counter of the Receiver process is at the matching channel’s receive statement, the rendezvous is accepted, and the sent value is copied into the local variable. These send and receive statements for rendezvous channels are executed atomically. Once the rendezvous completes, the location counters in both processes advance to their next instructions.

I know this might feel like a lot of information, don’t worry—we’ll walk through it step by step below.

Let’s start again. As indicated earlier, this is our code at the start:

Initially, both location counters point to the first instruction. Suppose the location counter in the Sender process reaches the send statement and offers to engage in a rendezvous. At this point, the Sender process becomes blocked because there is no matching receive statement yet.

Now, the location counter in the Receiver process advances to 7:

At this point, the rendezvous is accepted, and both statements execute atomically. The value 10 is sent on the channel, received by the Receiver process, and copied into its local variable. Once the statements are executed, the location counters in both processes advance to their next instructions.

We can also send a channel through another channel. This allows one process to pass a channel to another process. Let’s take a look at the following code:

chan ch = [0] of {chan}

active proctype P(){

chan localch = [0] of {byte}

// sends a channel

ch ! localch

byte data

// waiting to receive data

localch ? data

// ensure data is 100

assert data == 100

printf("Data = %d \n", data)

}

active proctype Q(){

chan localch

// receives a channel in localch

ch ? localch

// sends 100 on localch

localch ! 100

}

We declare a global rendezvous channel, ch, which is used to exchange other channels. In process P, we send a channel of type byte on ch. After that, P waits for localch to receive data into the variable data (as seen at line 15).

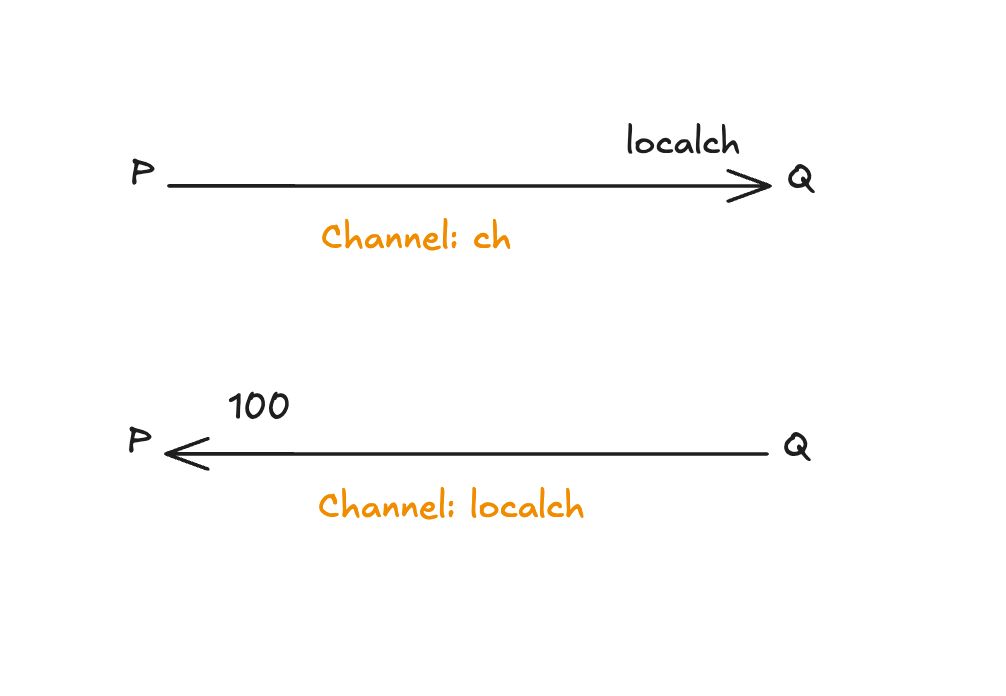

The following visualization helps illustrate what’s happening here:

Consider the lines with arrows as channels. Process P sends localch on the channel ch, and process Q receives it. Then, Q sends the value 100 on the channel localch, and P receives it.

One important note: in such scenarios, if the process that instantiated the channel terminates, the corresponding channel also disappears. Any attempt to access it from another process after this will fail and result in an error.

Hopefully, this provides a general understanding of how rendezvous channels work in PROMELA. We’ll build on these concepts in future articles.

Please email or tweet with questions, ideas, or corrections.